People who come to see Pratt Mansions Fifth Avenue for the first time—especially guests at weddings and parties—nearly always remark that they are reminded of Paris. And they are right. All three mansions have the cut stone (“rusticated”) surfaces that you see all over Paris. The classically French glass and wrought iron doorways are beneath beautifully carved cartouches displaying the building numbers—all flourishes that are hallmarks of Beaux Arts architecture and very favorite features of mine that I never tire of.

Walking along the surrounding streets—the neighborhood is known to NYC natives and tourists alike as Museum Mile or Carnegie Hill—and you’ll quickly spot more than a few buildings that closely resemble 18th century Bordeaux chateaus. Plus, lots of carved stonework featuring cherubs, angels and dragon fish.

But, while I am as much a Francophile as anyone, I think the neighborhood is more than just “Paris lite” and I was pleased to see that Michael Kimmelman of the New York Times agrees with me. Kimmelman points out in his charmingly detailed New York Times article “Take a Tour of New York’s Museum District” that what makes this particular neighborhood of New York so delightful and fascinating is not the singular influence of the French Beaux Arts style, which is undeniably prevalent, but the very rich combination of influences. That chateau that looks like it came from Bordeaux is sitting next to a building that looks like it was shipped from Bedford Square, London. And next to that are two buildings that could have arrived straight from Beacon Hill Boston. The overall effect is, as Kimmelman notes, a certain ineffable “Americanness.”

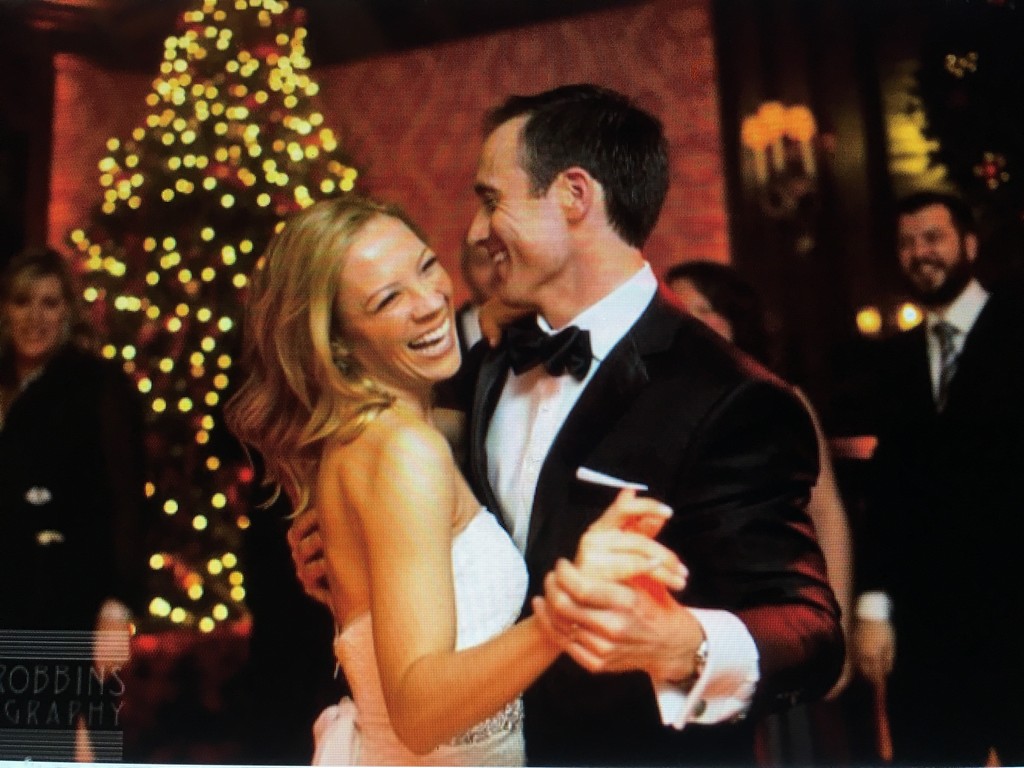

Brides often tell me that they chose Pratt for their wedding because they wanted a feeling of a bygone era, as if they were in an Edith Wharton novel. It’s true. While the Beaux Arts style that you see all over the neighborhood is unmistakably Parisian, it’s also a visual metaphor for America’s Gilded Age, the explosion of wealth that began after the Civil War and that Wharton captured in novels like the House of Mirth and The Age of Innocence. And that’s also the history of the Pratt Mansions.

The three buildings that make up Pratt Mansions were all constructed within a few years of each other, starting in 1901. They were all built separately, all by renowned architects, and were all occupied by incredibly wealthy families.

The first building to go up (1028 Fifth Ave), the mansion on the corner of Fifth and 84th Street, was to be the retirement home for Jonathan Thorne, a wealthy New York leather merchant. It’s a classically proportioned, five-story building with the hallmark, Beaux Arts, rusticated stonework on the ground floor, then a two-story façade that bows out over the entrance, a fourth-floor balcony to enjoy the views over the recently completely Central Park, topped by a decorative cornice and dormers embedded in a steep mansard roof.

The architect of 1028 Fifth was the well-known Charles Pierrepont Henry (C.P.H) Gilbert, who also figures prominently in Kimmelman’s story as the architect of the chateau-like Ukrainian Institute on 79th Street (where he included a lot of carved dragon fish) as well as the Warburg Mansion, now the Jewish Museum, on 92nd Street. Compared to the many flourishes on those buildings, his design of 1028 Fifth is downright restrained.

While Gilbert did not design the other two mansions to the south, at 1027 and 1026, you can see his influence all over them. The architects Joseph Van Vleck and Goldwin Goldsmith (the latter had worked for McKim, Mead & White) took pains to line up the mansard roofs, the cornice line and the windows across all three buildings. They retained the cut stone along the first floor and the dormers embedded in the roof, but faced the wider 1027 building in a flat façade of white marble and lovely iron balconies and then, in the third mansion (1026), more closely echoed the design of Gilbert’s original building with a two-story bowed bay of limestone and another, charming cast iron balcony. The result is that the three buildings, while very different, all work together architecturally and indeed in the interiors, as you easily pass from one to another, you might think they were all created as one building.

All three buildings changed hands many times over the years and the roster of occupants reads like a Who’s Who of New York’s Gilded Age including Thornes, Pratts, Vanderbilts, Milbanks, Kinglands, Clarks, Dukes and Whitneys. Through successive purchases, from 1925 to 1950, they became part of the Marymount School of New York, an independent, Catholic day school for girls (which is what they are today) while also being available for weddings and other private functions as The Pratt Mansions.

I get a thrill each day walking into these buildings. I love turning the corner on Fifth Avenue and seeing Pratt on one side facing the grandeur of the Metropolitan Museum on the other. I love the stonework on the outside and the beautifully detailed marble and woodwork inside, especially in the public rooms that are used for weddings and parties. Brides who are married here adore being photographed on the balconies overlooking the Met and Central Park. (Look at the Home page or the Gallery.)

Kimmelman notes that in House of Mirth, Edith Wharton’s heroine turns a corner and sees grand new houses, “fantastically varied, in obedience to the American craving for novelty.” Americans at the turn of the century, Kimmelman says, “felt they had inherited the whole of Western civilization, that it was theirs to do with as they wished.”

What makes it all the more bittersweet is that this period didn’t last long. The Depression and World War II brought a halt to new construction in New York for decades. But well before all of that, most of these mansions were headed toward the chopping block to make way for the modern luxury apartment houses that now line Fifth Avenue. The mansions that make up Pratt Mansions are among the last to remain (now, thankfully, protected with landmark status), a reminder of a bygone era of (until recently) unmatched opulence and inequality, but also one that set a standard for elegance in the buildings we now enjoy along New York’s celebrated Museum Mile.